Jean-Christophe Rufin is well known and appreciated in France, Africa and Brasil but unknown in the English speaking world. It is a pity.

Camino Downunder is reviewing and critiquing his latest published text: Immortelle randonnée – Compostelle malgré moi – “Immortal trek – Compostela despite me“ (Always challenging to appropriately translate the title – too much creativity in the translation and it can mislead, whilst staying too close to the original text and that too, distorts the real meaning).

For English speakers it is important to understand that in French le Chemin de Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle means el Camino de Santiago in Spanish (St James Way). And the city of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain is called Saint-Jacques de Compostelle in French.

Immortelle randonnée – Compostelle malgré moi was published by a small French publishing house Éditions Guérins, located at Chamonix in the Alpes in France this year in March and when our French friend’s son of the reviewer arrived in Sydney in April (2013), he was given this new publication, hot off the presses.

So, who is Jean-Christophe Rufin?

Born in the French town of Bourges (geographically in the middle of France) in June, 1952 and soon after birth, his maternal grandparents care for him until he was later reunited at the age of 10 with his mother, in Paris. At 15, in 1967 he decides to study medicine because he is inspired by the South African transplant doctor Christian Barnard and the world’s first heart transplant. He becomes a specialist neurologist and psychiatrist but before undertaking medical specialisation, he chooses to go to Tunisia (his first contact with Africa) and instead of doing his compulsory French National military service in France, he goes to Tunisia in a non-military capacity as an aid worker in a third world (developing) country.

Alongside the internationally well-known Bernard Kouchner, Jean-Christophe Rufin is one of the early doctor pioneers for Médecins sans frontières (MSF) (Doctors without borders) and has traveled many times to East Africa and Latin America on humanitarian and covert missions. He has also worked for the French Government in various capacities in France and overseas; such as France’s cultural attaché to Brazil (1989-1990) and knows the Portuguese language very well; French Ambassador to Senegal and Gambia (2007 – 2010) and many other executive management positions in French government administration.

He has been a teacher and lecturer at some of France’s most prestigious and élite tertiary institutions and since the middle of the 1980s he has been a prodigious writer in all genres from novels, historical novels, essays both fiction and non-fiction. Such is his reputation as a brilliant writer, that Rufin in 2008 was elevated to being one of “Forty Immortals/les Quarante or Les Immortels” (until death) – due to his successful nomination and election to France’s most prestigious cultural/ language institution the Académie française – the final guardian and promoter of the French language, founded in 1635 by Cardinal Richelieu, chief minister to Louis XIII.

Jean-Christophe Rufin: dressed in the green costume “l’habit vert” – the regalia worn by the 40 members of the Académie française

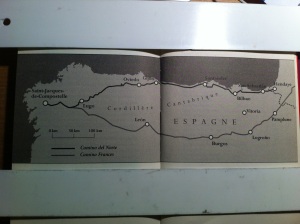

Immortelle randonnée (Immortal trek) recounts Rufin’s story about his connection to the Spanish pilgrimage tracks (he undertook the Northern route), commencing in France in May, 2011 from Hendaye (see map below) near the Spanish/French border, then walking through San Sebastián, Bilbao, Santander, Gijón, Oviedo, Lugo and on to Santiago de Compostela and his subsequent conversion into it becoming an obsession. And finally some 23 months later his book Immortelle randonnée – Compostelle malgré moi is published.

In the first half of 2013 Immortelle randonnée sold over 118,000 copies (source: Edistat) and it was from April, 2013 only when it had arrived in the book stores and sold on-line. In the first semester of 2013, this non-fiction text about a French person’s discovery and initiation of the ‘Compostelean’ attractions achieved the number 14 best seller list of all books foreign and French, fiction and non-fiction sold in France (source: Edistat).

In July this year, the writer presented a paper (The Pedagogy of the Pilgrimage Routes in France and Spain http://caminodownunder.com//library/Pedagogy_Pilgrimage_Routes.pdf) at a language conference hosted by the Australian Federation of Modern Language Teachers Association (AFMLTA) in Canberra and whilst researching and preparing for his presentation was struck by the 10 stage schematic model for engagement (see below) with a pilgrimage track (before, during and after) whilst reading in tandem Jean-Christophe Rufin’s text.

In Grossman’s paper, the pilgrim undergoes the following 10 steps of engagement and development. Broadly speaking this is how Rufin’s text: Immortelle randonnée – Compostelle malgré moi is set out; but with variations to account for creative writing, freedom of choice for the subject/person, with analytical and philosophical reflections peppered throughout the book.

THE TEN STAGE PROCESS FOR ALL INDEPENDENT WALKING PILGRIMS

- DECISION-MAKING/MOTIVATION

- PREPARATION

- DEPARTURE

- TRANSITION

- JOURNEY

- ARRIVAL

- RETURN

- RE-INTEGRATION

- WORKING UP THE EXPERIENCES and

- LASTING EFFECTS.

PREPARATION: Chapter 1 is «L’organisation» and we are informed he knows very little about the Camino de Santiago, apart from his image of it as being an ancient track with pilgrims walking solo.

He discusses in some detail his nascent knowledge about the Camino de Santiago. As he starts his «PREPARATION» he begins to understand what the purpose and nature of the credential (the prilgrim’s pass or “credencial” in Spanish) is whilst being a pilgrim. And most importantly:

«On découvre alors que le Chemin est l’objet sinon d’un culte, du moins d’une passion, que partagent nombre de ceux qui l’ont parcouru.» (One discovers that the Camino, if it isn’t a form of cult workship then it is at least a passion which is shared by those who have walked it). During his preparation period the French writer discovers “Toute une organisation…” (A whole organisation…) «Le chemin est un réseau, une confrérie, une internationale.» (The Camino is a network, a veritable confraternity of humanity.)

However, throughout this first chapter and as well as in every other of the 32 chapters there is analysis, synthesis, philosophical meditations, linking the present to the past with his every step along the Northern Camino route. His writing style profoundly engages the reader whether he/she may have undertaken the Camino de Santiago or not. He does not hide his foibles (e.g. his insomnia) nor is he falsely modest about his qualities and abilities to successfully walk the distance and do it with some panache. Along the Camino track he is (and this is not surprising because it is a common characteristic among independent, modern foot pilgrims) one day misanthropic and the next day philanthropic – wanting to be or not wanting to be with people.

DEPARTURE: Chapter 2 is «Le point de départ»

For Rufin, as it is for every single pilgrim-walker: deciding where to begin – where to put the first step. For the independent pilgrim, time allowed or permitted will invariably dictate where they will begin. The writer puts it succinctly: «C’est la raison pour laquelle, vers Compostelle, l’essentiel n’est pas le point d’arrivée, commun à tous, mais le point de départ. (…) La question qu’ils se posent est “D’où es-tu parti?” Et la réponse permet immédiatement de savoir à qui l’ont à affaire.» (It’s for that reason that the aim of getting to Compostela, is not the arriving which is everyone’s aim, but where they leave (…) The question people ask is “Where did you start?” And the response then immediately informs the questioner who he is dealing with.)

Rufin truly and deeply understands that the greatest, most profound and long-lasting effects of pilgrimage in our age depends on doing very long and over many weeks challenging pilgrimages. Nearly ten years earlier the American Conrad Rudolph (professor of medieval art and chair of art history at University of California) said exactly the same thing in his text Pilgrimage to the End of the World – published in 2004 by The University of Chicago Press: “This is why pilgrimage must be done on foot, never on bicycle; why you must stay in refugios, not in hotels; and why the journey should be long and hard.“

Il faut en effet reconnaître que le temps joue un rôle essentiel dans le façonnage du «vrai» marcheur. p. 15 One has to recognize the essential role which time plays in shaping an authentic walker.

Le Chemin est une alchimie du temps sur l’âme. p. 15 The Camino track is an alchemy of time poured over the human soul.

Il perçoit une vérité plus humble et plus profonde : une courte marche ne suffit pas pour venir à bout des habitudes. Elle ne tranforme pas radicalement la personne. p. 16 He (the pilgrim) perceives a more basic and profound truth : a short walk is not enough to really affect his habits and dispositions. It does not fundamentally change the person.

DECISION-MAKING/MOTIVATION (revisited): Chapter 3 «Pourquoi ?» (Why?)

In Immortelle randonnée, Rufin cleverly reverses the chronological steps by explaining his reasons for undertaking the Compostela pilgrimage. Essentially, he explains his original motivations by simply wanting to do a very long solo walk. His decision in doing “Compostelle malgré moi” (Compostela despite me) is due to the «St Jamesian virus» which has deeply infected him.

“J’ignore par qui ou par quoi s’est opérée la contagion. Mais, après une phase d’incubation silencieuse, la maladie avait éclaté et j’en avais tous les symptômes”. Not knowing by what means or by whom had infected me. However, after a silent incubation period, this sickness exploded and I was presenting with all the symptoms.

Camino Downunder in Australia and New Zealand has always had in its classes, participants demonstrating those very same characteristics: the seemingly benign Camino seed somehow got implanted in the person’s being, laying dormant, sometimes for many years; and suddenly it explodes internally to then dominate behaviour by turning it into a commitment – the first act (DECISION-MAKING/MOTIVATION) in this ten stage process.

TRANSITION: Chapter 5 «Mise en route» (Starting up)

Having made the decision to do le Chemin du Nord – el Camino del Norte, thanks in large part to the volunteer person manning the front desk in a Paris located Friends of the Camino office. In May, 2011 Rufin leaves Paris by TGV and gets to Hendaye on the south-west Atlantic coast. Like most pilgrims, arriving at the head of the walking track at Hendaye (the closest French border town to crossing over into Spain at Irún), Rufin splurges modestly on a one star H (French symbol) hotel and in his own self-deprecating words: «restons modeste, tout de même».

In Grossman’s language conference paper he notes that in TRANSITION the pilgrim-walker leaves his familiar environment when he places his first foot on the designated pilgrimage track and the subject/person is now feeling a sustained range of emotions and feelings; from the positive to the negative…”An explosion of sensorial stimuli...”

Jean-Christophe Rufin writes:

Mes émois de pèlerin novice étaient puissants. J’avais envie de chanter. Il me semblait que, d’ici peu, j’allais traverser la forêt de Brocéliande, croiser des chevaliers, des monastères en pierre. Inutile de préciser que je m’exalte vite. P. 37 My excitement as a novice pilgrim was powerful. I wanted to sing. It seemed to me that, without much effort I was going to walk into Brocéliande forest (NB the legendary Breton forest where Merlin the Wizard and Viviane the fairy lived, according to the stories of the Round Table) and to pass by knights and stone monasteries. Not necessary to labour the obvious: I become excited quickly.

JOURNEY: Chapters 6 to 31 of Immortelle randonnée – Compostelle malgré moi are 200 pages of vivid descriptions of the Camino del Norte up to Oviedo (the good, the bad, the ugly and the exquisite) and which then turns into the Camino Primitivo from Oviedo to Santiago de Compostela via Lugo.

The insightful comments about the locals and the many pilgrim hostel wardens; observations of his many fellow pilgrims (such as, the female Australians walking in a group with their Austrian female counterparts); Rufin’s own emotions and feelings, his philosophical analyses, plus his self-deprecating comments producing a true masterpiece of writing; guaranteeing to engage 100 percent of the time any reader of the French language (classic or modern) and whether they are interested in the Camino de Santiago or not. The reviewer was awed by Rufin’s text from start to finish because he is simply a brilliant writer of the French language. To others who do not have a passion for the French language but are passionate about the Spanish pilgrimage routes, this text would still take pride of place in their treasured pilgrimage library. One can only hope, sooner than later, that an excellent translation into English will happen for an English audience in the English-speaking world.

This is the map in Immortelle randonnée: showing the Camino del Norte + Camino Primitivo + Camino Francés (pp. 260-261)

During the JOURNEY, Rufin writes movingly about an alternative/variant track high up in the Asturian mountains, recommended to him by a female grocery/hostel manager in order to walk a summit pass before getting to Salime. Rufin looses himself in the moment and he is between heaven and earth. Nature’s physical beauty here is so intense and so overpowering:

dans cet espace ouvert, saturé de beautés, à la fois interminable et fini, le pèlerin est prêt à voir surgir quelque chose de plus grand que lui, de plus grand que tout, en vérité. Cette longue étape d’altitude fut, en tout cas pour moi, le moment, sinon d’apercervoir Dieu du moins de sentir son souffle. P. 192 …in this open space, saturated with beauty, at the same time being both finite and infinite, the pilgrim is ready to accept the truth of a presence which is bigger than him and bigger than anything existing. This long walking section high up in the mountain was for me the moment, if not then of glimpsing God’s presence, then at least feeling his breath on me.

Jamais le monde ne m’avait paru aussi beau. P. 194 Never the world had appeared to me as being so beautiful as it was now.

ARRIVAL: In Chapter 32 (the last chapter) appropriately called L’arrivée in French, Rufin writes about himself, but could very easily be writing for all authentic, long distance and independent pilgrims.

Yes definitely it’s good arriving, but the let down soon sets in and then begins the challenge of “RE-INTEGRATION“. After much reflection, the reviewer states that arriving in Santiago de Compostela is metaphorically death and failure. If “arriving” means you can no longer go further: that can then be construed as an allegorical ‘death and failure’. The pilgrimage journey is finished, extinguished or destroyed by the pilgrim’s very success in arriving. That is the paradox of pilgrimage and arriving – pilgrimage must, by definition finish one day. And that is precisely why the authorities (secular and religious) in Santiago deeply understand this pilgrimage paradox: arriving is the death and failure of each person’s pilgrimage. And that explains why the ex-pilgrim is offered a number of inducements to stay as long as possible in this magical city. However, staying more than three days in Santiago as an ex-pilgrim becomes boring and meaningless.

The writer of Immortelle randonnée briefly discusses how arriving in Santiago affects him:

Car tout concourt à le rompre, dès lors qu’on est «arrivé». Les charmes et les beautés de Compostelle ensevelissent les souvenirs du Chemin. Le corps reprend sa nonchalance urbaine : on traîne dans les ruelles et, bientôt, on se surprend même à acheter des souvenirs…p. 256 Because all competitions break the ribbon on arriving at the end. The charms and attractions of Santiago bury the memories acquired along the pilgrimage track. The pilgrim’s body returns to its city-like listlessness : one wanders around aimlessly in the old city and you surprise yourself by buying some souvenirs…

In Rufin’s last chapter comprising 10 pages the writer in few words coherently and accurately describes the last 5 post schematic model stages after the JOURNEY and ARRIVAL have been achieved: RETURN; RE-INTEGRATION; WORKING UP THE EXPERIENCES and LASTING EFFECTS.

In a few profound words, Jean-Christophe Rufin deeply reflects on his pilgrimage experiences and their lasting effects. On returning home he now applies his new practical and philosophical principle which he calls “la philosophie de la mochila” + “la mochila de mon existence” “Mochila” is the Spanish word for the backpack one carries as a pilgrim-walker. In other words, “LESS IS MORE”. He returns to his home in the French Alps and for the very first time in his life, he is brave enough to finally get rid of accumulated stuff (things, projects going nowhere etc.). He also addresses his fears which have accompanied him for a lifetime.

What is extraordinary with Rufin’s text is the fact that whilst walking over 800 kilometres from Hendaye to Santiago de Compostela he had NOT once ever wrote down any of his observations, feelings and analysis. He tells us this emphatically and explicitly and is in fact quite disparaging of his fellow pilgrims who write each day after their many hours of walking. He had not wanted at any stage to produce a book about his pilgrimage until returning home and with the snow all around him and being snow bound in conversation with two people who happen to be connected to Éditions Guérin at Chamonix in the French Alpes; that he is persuaded to put pen to paper and he tells us he remembers everything that he had experienced:

Dans la prison de la mémoire, le Chemin s’éveillait, cognait aux murs , m’appelait. Je commençai à y penser, à écrire et, en tirant le fil, tout est venu. p.258 In the prison of my memory, the Camino was revealing itself, it was bashing down the walls to get out, it was calling out to me. I started to think about it, to write, and in pulling on the linking thread, it all came back to me.

In his penultimate sentence, Rufin informs the reader he will be doing another Camino track soon.

The reviewer does not know if there will ever be a translation into English of this text. However, if you do not know French and you have been looking for a compelling reason to undertake serious French language studies, then look no further: Immortelle randonnée – Compostelle malgré moi is a modern masterpiece.

Reviewer: MARC GROSSMAN

Note: All translations into English from the French in this post is by the reviewer Marc Grossman